We all know that fishing is not necessarily about what we catch. We might collect PBs and fine waterside memories, but we also like to read about our sport, watch films on it, and collect tackle and other piscatorial artefacts like carvings or artwork.

We all know that fishing is not necessarily about what we catch. We might collect PBs and fine waterside memories, but we also like to read about our sport, watch films on it, and collect tackle and other piscatorial artefacts like carvings or artwork.

Perhaps artwork is especially satisfying if it is personal, if you have some link with what has been painted or drawn. At Thomas Turner we’d love to hear of your own treasures, but here is mine to kick the thought off for us…

I visited India virtually every year between 1989 and 2013/14, ostensibly pursuing mahseer, but there was so much besides, as you can imagine in that absorbing country.

Many of my trips took me to the North, to the rivers of the Himalayas, but mostly I went down South to the legendary River Cauvery.

It was on that river, three hours out of Bangalore, that I led trips for nigh on twenty years. These were extraordinary times in every sense. The fishing was unparalleled, as was the wildlife, but the people made it special, both anglers and my Indian friends that I came to love over my time there.

There were many extraordinary anglers, providing many tales, but perhaps the most unforgettable was Sir Michael Tims, who visited with me in 2006. Michael was mid-seventies at the time, and had retired from service with the Queen.

He was continually worried that his age would hold us back, but he was as fit as the fittest and caught the most fish too, all done with charm, grace and complete aplomb. He had a wonderful sense of fun.

One of the group had brought a satellite phone (before the jungle could accommodate mobiles this was) and offered it for anyone’s use when he finished with it.

Michael was given first option to contact his wife (at Hampton Court), but first he auditioned the guides to choose the best at making leopard noises. I was given my lines and then he phoned home.

“Having a wonderful time, darling”, he gushed before nodding to Bola, the guide, to make his fearsome growls down the line.

I was then “on”, shouting “Michael, Michael, run for your life, it’s a man-eating leopard”. “Got to go, darling”, Michael said and hung up. Hilarity all round until Michael dialled again to put his dear wife out of her misery.

The phone was dead, battery kaput. A local lad was paid handsomely to cycle three hours to the nearest STD phone to explain the prank to Lady T!

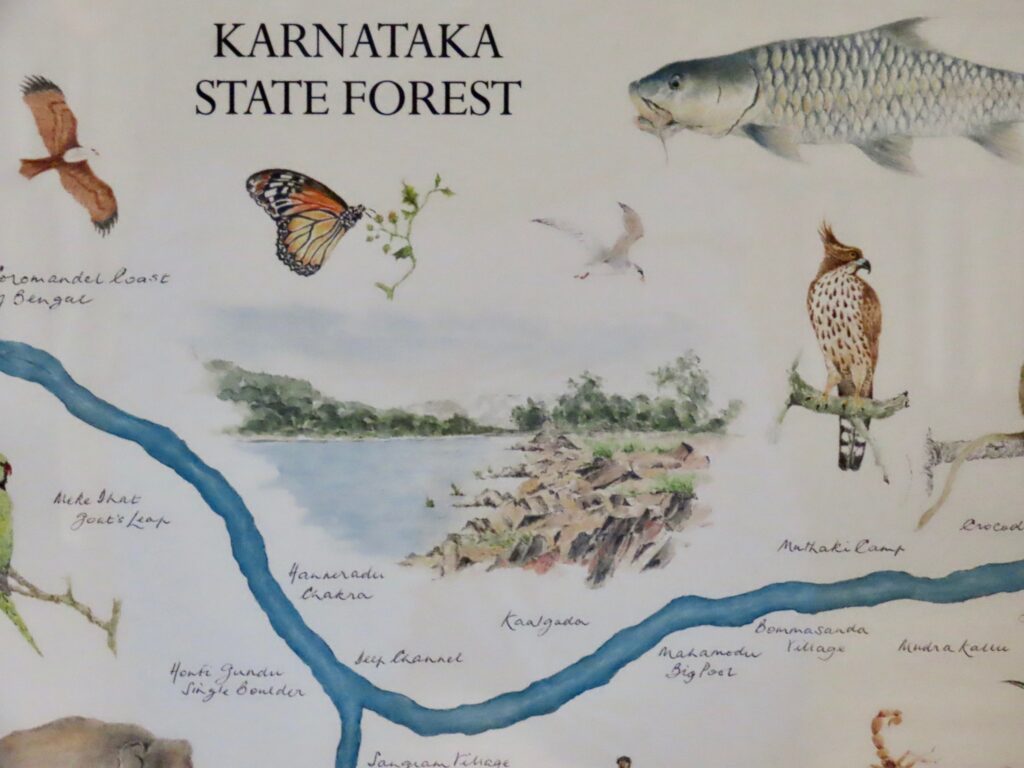

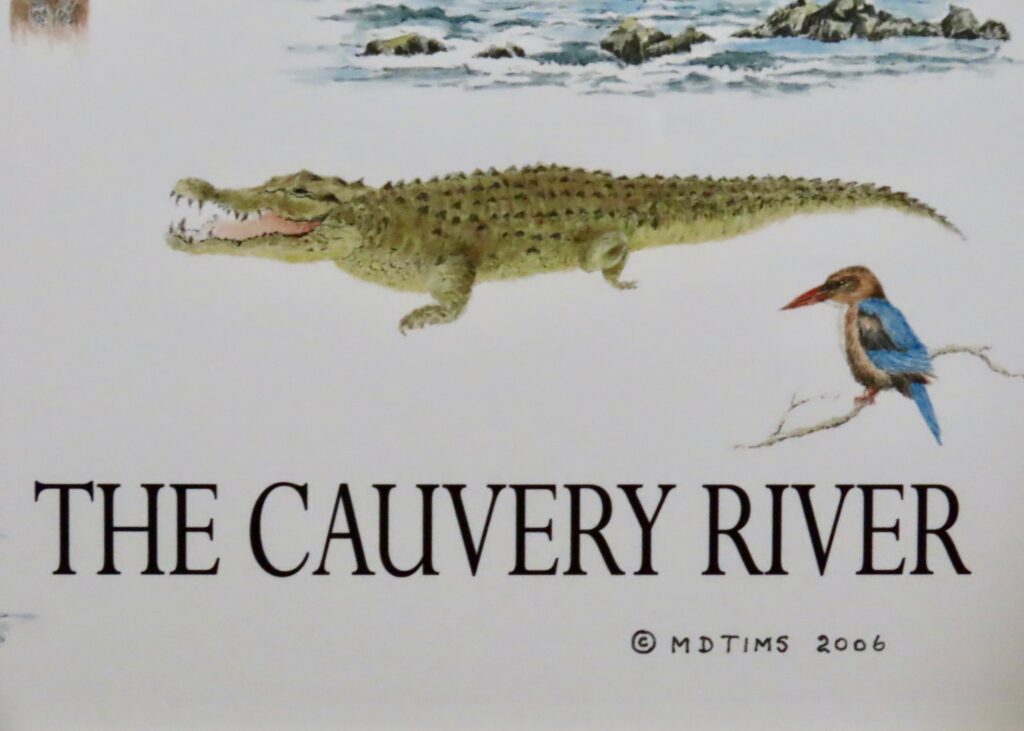

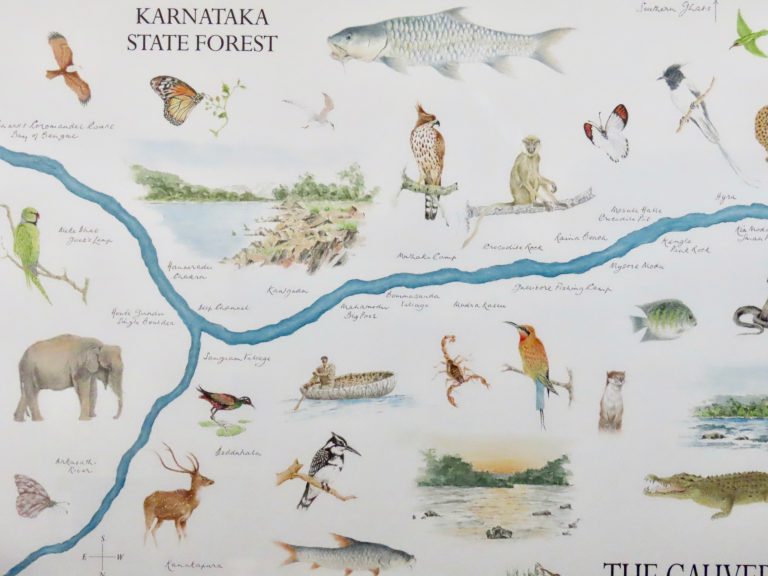

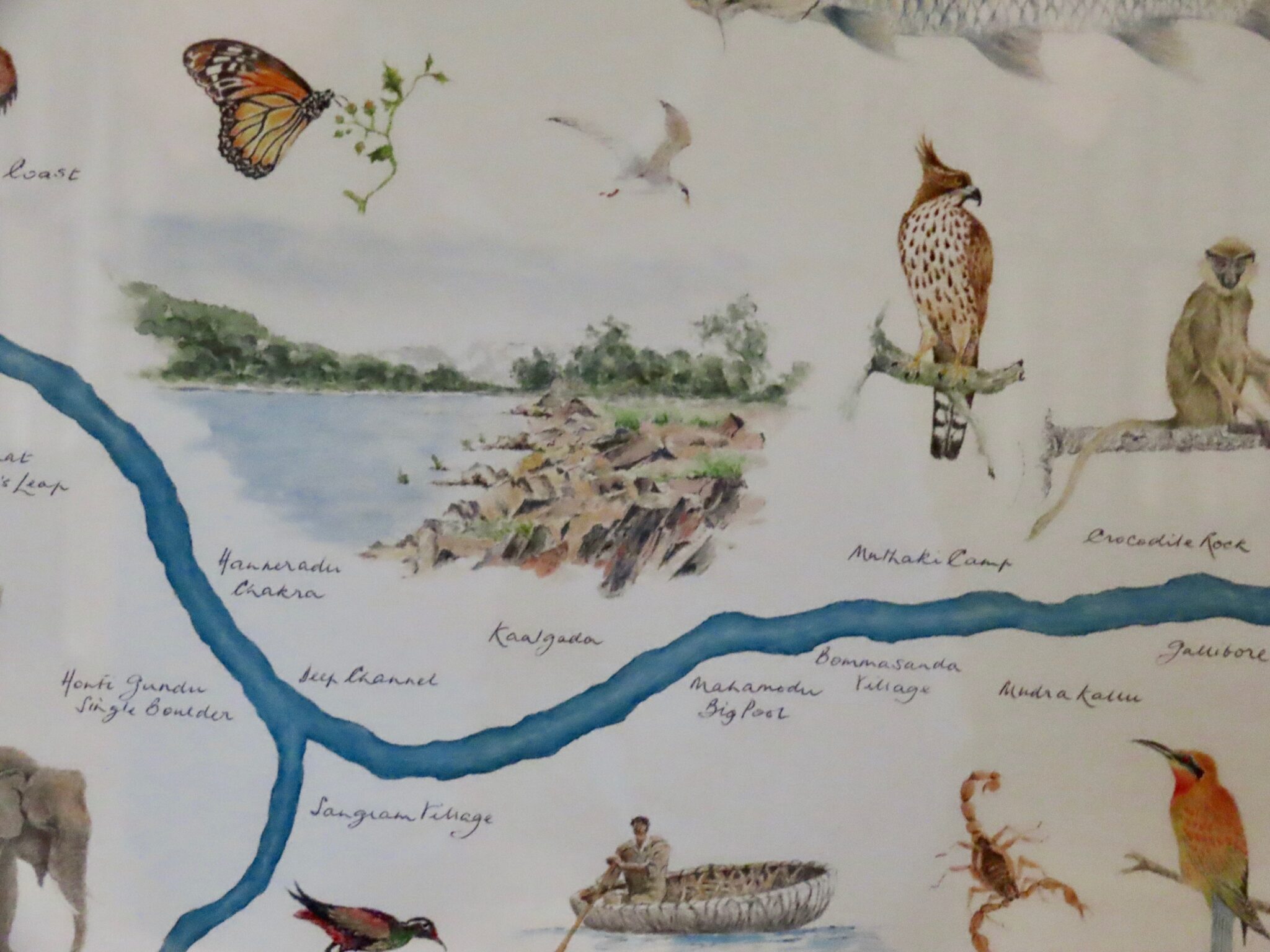

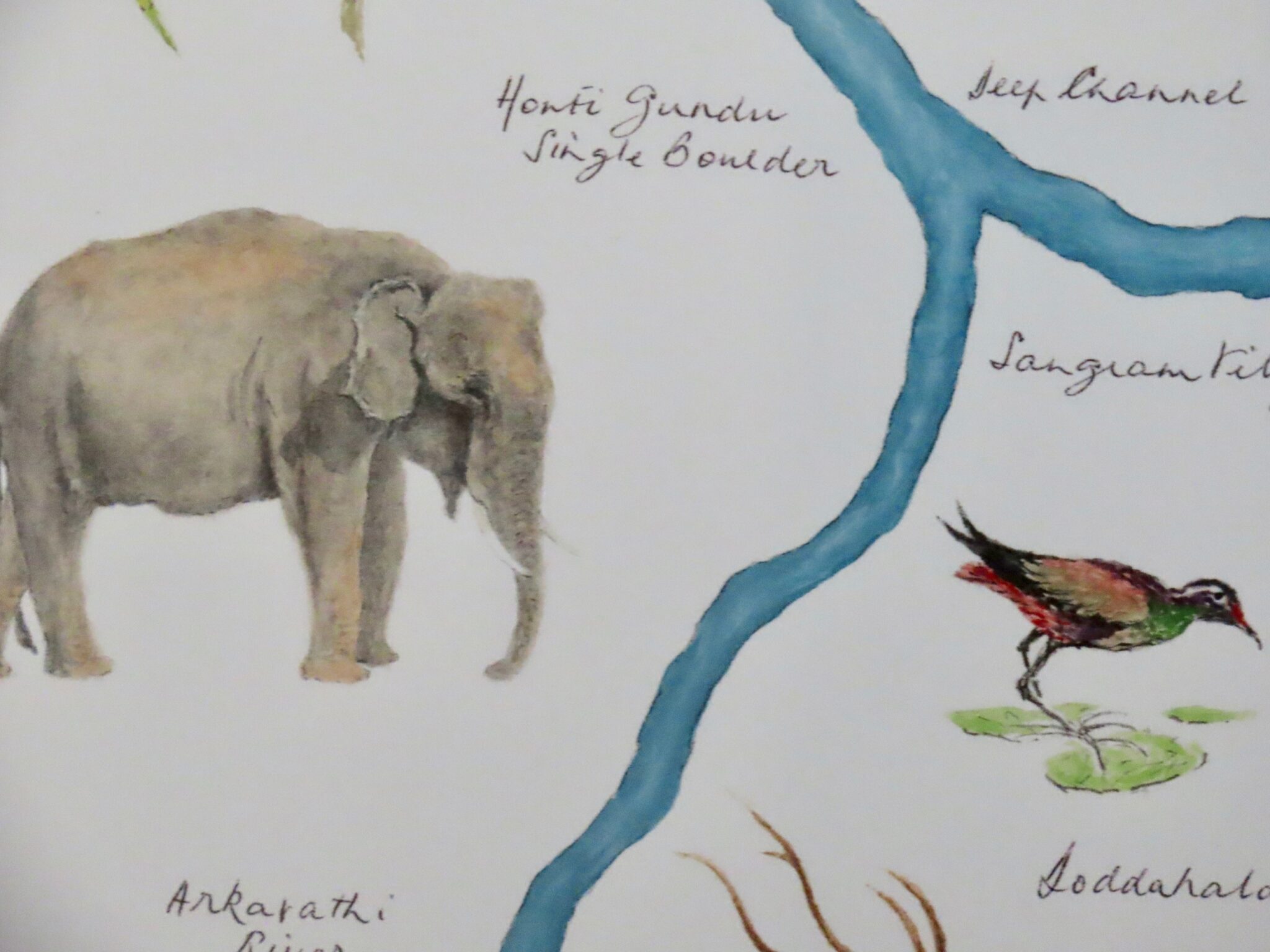

More seriously, Michael proved himself to be a fine artist and in camp, he set himself to create the visual record you see here. His idea was to commission a hundred prints that would be sold to provide funds for a local school we were trying to establish.

I hadn’t seen the work for 15 years and had near forgotten about it when just last week, dear friend Ian Miller gifted me print number 1 out of the 100.

Just the sight of it brought a tear to my eye, and the most vivid of memories to my mind. I drank in, again, the wonderful detail of the drawings and how Michael had captured the whole essence of the Utopian valley.

The coracles, the crocs, the tumbling rapids, and the giant fish were all there in their glory. Yes, indeed, a wonderful gift and reminder of perhaps the best years of my life.

But there are two shadows that hang over the story of the Cauvery.

I don’t know how many prints were sold, but I do know that within two years around £12,000 had been raised in order to establish a basic school that the river children desperately needed.

We trusted people on the ground with that hard-earned money and it all disappeared, dribbling away in bribes and handouts and not a brick was laid.

The shame of this I still carry, and when I am involved with good works today I ensure I am far more hands-on.

Secondly, the Cauvery was a river under threat from India’s whirlwind development, and the mahseer, especially the historic “golds”, were ever more restricted in their range.

It’s a long story but several years ago, the government bodies, in their wisdom and acting upon environmental advice, closed down our fishing camps.

Now, back in the Eighties when anglers first started arriving on the Cauvery, there were no camps, and the river was netted, poisoned and dynamited with the mahseer being taken to market.

Over twenty five years, the camps provided proper employment, the poachers became guides and watchers, and mahseer numbers soared.

By banning the fishing, all this progress is being reversed, and the environmental lobby is achieving the exact opposite of what it set out to achieve. This message is starkly clear to all of us, and the point hardly needs to be laboured.

Today, I wonder about that dear, talented artist. I’m thinking I must look him up. Yes, he would be a man of ninety or so now, but such a character as Michael lives by his own rules and time-scales.

My guess would be he is still fit as a trivet. I also wonder where the original painting might be, and where the other, numbered prints might reside… perhaps you have one yourself even?

So, there you go. That’s our story from Thomas Turner. Now, over to you!