I am, of course, obsessed with the Wye now, like I was as a child in the very early Sixties. Then, in my childhood, I was fortunate to spend time on the river for four years running, and though I was too young to consider catching the enormous salmon I saw, their image has never left me. When I came back to the river in the Eighties, I still on occasion saw monster fish, which I completely failed to catch, but I remained fascinated by the history of big Wye salmon, a passion stoked by conversations with veteran guides who claimed to have known or witnessed Pashley fishing back in the immediate post-War years. Robert Pashley famously fished the Wye between 1897 and 1951, caught over ten thousand salmon from the river, including many at forty pounds-plus. It is hardly a surprise that such a man became, and remains, my hero.

Now I live in Herefordshire, I spend some time most days on the Wye, for one reason or another and this year, 2021, I have to say that despite all the problems this mighty river faces, I have seen more salmon than in the past. Indeed, yesterday, despite searing heat, I counted ten different fish along a mile beat in a three hour stay. What I do not see many of are anglers out fishing for salmon, me included!

Last night, I poured a gin and considered. Would Pashley catch salmon from the Wye today if he were alive and in his prime, perhaps in the 1920s? Would that exquisite technique and supreme knowledge of the Wye still net results in these shrunken, salmon-starved times? Naturally, there is one book you have to go to for any answers, and that would be The Tale Of A Wye Fisherman by H A Gilbert. Gilbert wrote in 1929 “Pashley is the Shakespeare, the Beethoven, the Leonardo da Vinci of Wye anglers”, and certainly those Wye men I spoke to way back were similar fans. You could argue that Pashley had unique access and endless time during a period when fishing was at its peak, but that would be churlish. Compared with the results of good contemporary anglers, Pashley still stands way out in front. It was generally considered that where a steady Wye fisher might take four fish, Pashley would have ten. But would he get any today, that’s my question? Well, I think he would, especially if he had the time to relearn the topography of pools, altered to some degree by seventy years of winter floods.

First, I suspect Pashley had a far greater reverence for salmon than some of us today. His dictum was always to keep out of sight of the fish, and never let them see you. He appreciated they could see like eagles in clear water, hence his camouflaged clothing and the way that he would skirt pools by many yards before creeping in to fish them down. He had the reputation for being reserved and abrupt, but in truth his aversion to being watched was down to the fact that few spectators knew how to behave like herons! I really like this fact. He was so aware of a salmon’s eyesight, that he would shuffle his feet and cloud the water as a fish came close to the gaff to avoid a last-minute scare. This is an angler who really rates his adversary.

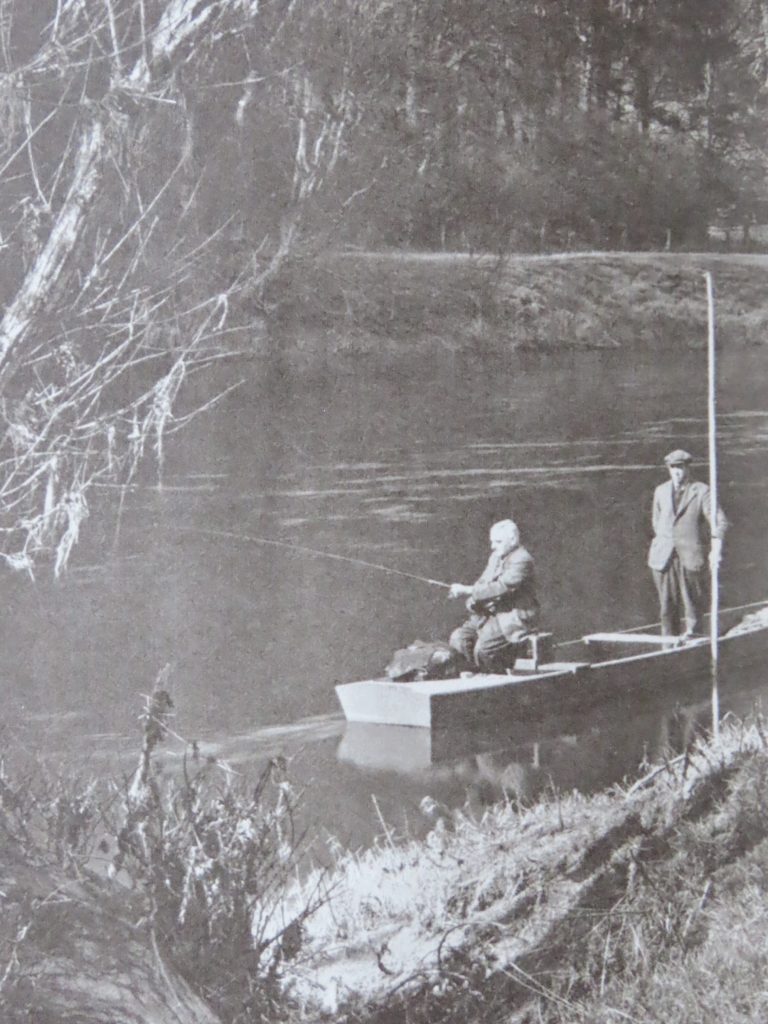

In the same vein, Pashley used a trout rod in his early days because he felt the disturbance caused would be minimised. This is very Icelandic and very softly, softly. An 11ft Hardy cane Perfection was his tool of choice and I wonder if I could find one today to use on the great man’s favourite pool… Equally, Pashley liked to wade, and realised his best days were behind him when he was forced by physical issues to fish from a punt. Yes, he forged a telepathic understanding with his boatman Jack Whittingham, but even so he knew the stealth of approach that wading afforded him was lost forever. Pashley liked to fish the Wye with the lightest touch possible, a ghost presence on the river, and that caught him fish only a heron could match.

Pashley realised what some salmon anglers do not. Salmon learn supremely quickly from their mistakes and about the things that constitute danger. He avoided those beats that had recently been fished because he knew salmon could not tolerate a hammering. He always held that the first cast was the best cast, and he went to great lengths to get that one right. He appreciated not just how quick a salmon is to see danger, but also how sensitive it is to feeling danger. He knew a salmon, a summer salmon, can feel anything “wrong” with a fly, lure or bait in an instant, and eject it with amazing force as a result.

There are other elements to Pashley too. His care of tackle was legendary and he never took chances with line or knots. His approach to every beat and every pool was rigorous, planned out, and methodical. Once a fish was hooked, in the eyes of observers, it was hardly ever lost, and Pashley would pursue a salmon through a forest of alders in pursuit. He was steely-eyed in everything he did and left nothing to chance.

This is commendable and sensible both, but what made Pashley a salmon god, in my view, was the connection he had with them, the respect he held them in. In modern parlance, I guess you could call Pashley a salmon whisperer, and that’s why I think he would have had a couple of those salmon I saw leap out yesterday.

Robert Pashley died only seventy or so years back. I wonder if there is anyone out there who knew him, or whose father perhaps fished with him? We are, after all, talking very recent history indeed, even if the face of fishing has changed so rapidly in the period.