By Malcolm Dutchman-Smith

In the course of the present century the name of Eddie McCarthy has become synonymous with the River Thurso so much so that, deservedly, he has been described regularly as “Mr Thurso”. During the last century, together with his grandfather David Sinclair and his cousin David Sutherland, all of whom occupied the post of “River Superintendent”, he was one of the most significant persons in the history of the river and can justifiably claim much of the credit for making it the outstanding salmon river it is today.

However, one has to look back to the 19th Century to find the person who was fundamentally responsible for establishing the river as a sport fishery and implementing the structure in which it has been fish to the present day. That person is nothing like as well-known as some the many other historical giants of the game fishing world who tended to concentrate their attention on the larger “classic” salmon rivers of the United Kingdom but certainly his contribution was equally impressive particularly as he was not born into wealth, title or privilege but was from a comparatively humble background and through his own skills, acumen and hard work changed the Thurso from what was a solely a commercial fishery into a one in which sports fishing came to play a major part that thereafter continued to develop until, ultimately, from 2006 it become exclusively a sports fishery.

William Dunbar was not a native of Caithness but came from Grantown on Spey, the son of a house carpenter who owned his own house. On leaving school he trained as a mechanic and might well have remained in that occupation, had it not been for the fact that his potential was recognised by one of the local lairds who recommended him for a post as an Excise Officer in the public service, in which capacity he served at various locations although he had aspirations to better himself in business.

Given the area in which he was brought up it was unsurprising that, from an early age, he became a keen salmon angler and he pursued this interest with vigour throughout his life, so much so that he was one of the intrepid band of Victorian anglers who ventured to Norway in pursuit of large salmon. There he used a 20 foot rod to such effect that he indicated that he would very much have liked to have lived there if only he could have mastered the Norwegian language. He rented fishing rights on the rivers Inver and Kirkcaig in Sutherland when he was living at Lochinver in the late 1840s.

Sport fishing for salmon in Scotland was practised before the 19th Century but the logistical and economic isolation of the far north-east corner, and in particular Caithness, meant that prior to well into the 19th Century it was not to any significant extent a feature and the extensive runs of salmon into the River Thurso were exploited for commercial purposes by netting (both the river and Loch More) cross lining, cruives, hecks and, in the estuary, by net and cobble. Added to that, in the early 19th Century was the introduction of coastal netting by “fixed engines” such as stake and bag nets. Little if any rod fishing was carried out in the early years of the 19th Century although its potential was to an extent recognise by some angling writers of the period such as Thomas Todd Stoddart.

In about 1850 William Dunbar moved to Thurso and took over Caskey’s Hotel (now known as The Royal Hotel, installing his wife as landlady. He embarked upon a number of commercial activities that ultimately included, farming, a canning factory for fruit and salmon, commercial salmon fishing in a number of areas, not merely the Thurso, and operating one of the earliest “sporting agencies” covering both salmon angling on the River Thurso and the shooting of game birds on the moors of Caithness. As will be seen he did not limit himself simply to providing the fishing and shooting but also the accommodation for visitors under “package terms”.

Dunbar was obviously aware of the opportunities for salmon angling on the river and for making profit from the enterprise. In 1852, together with his friend and very experienced salmon rod Capt WP Gordon Cumming he explored the potential by fishing with the fly from the start of the season in early January until the end of March. Always alert to the need for good public relations and advertising, he ensured that the results were published in the John O’Groats Journal of 26 March 1852 in a lengthy note recording their capture of some 90 salmon, the largest of which was 28 ½ pounds and his best day, one in which he caught 11. The 2 rods caught a total of 366 salmon during the season on what was clearly then essentially a spring river as only 44 of them were caught after the end of May and no fishing at all done after August.

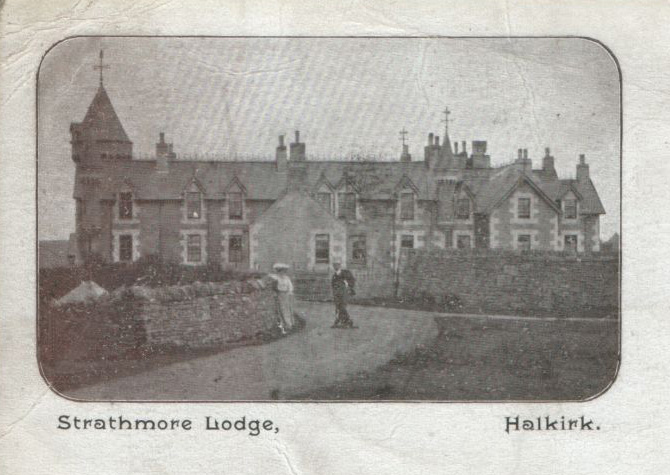

Being satisfied that the enterprise was financially viable, he negotiated with the proprietor of the river, Sir George Sinclair and particularly his son (later himself the proprietor with the title Sir Tollemache Sinclair) and on 16 September 1852 acquired his first “tack” or lease of the angling on the river for a period of 19 years. Also included was possession of Strathmore Lodge, a shooting lodge situated alongside the river in its upper reaches which he could use for accommodation of anglers fishing in the spring and guns shooting on the moors in the summer and autumn.

He canvassed the fishing friends and acquaintances that he had made in connection with his own angling trips, and was able to develop a clientele ready and willing to make the somewhat arduous journey to Caithness and to fish the Thurso with the fly, notwithstanding that it was not the fast flowing type salmon river such as the Dee or Spey, and indeed had a number of stretches of slow flowing canal like water.

He had acquired the rights over some 26 miles of fishing and he recognised that in order to ensure fairness between rods and to give a variety of different water to fish he should operate a rotating beat system over the seven or eight beats that he established. These were single rod beats and so it could hardly be said that the river was overfished. Visitors were wealthy individuals who had both the money and the time to devote to their hobby. He offered rods for the season or the month if they were not being fished by the annual tenant. He provided Gillies (initially referred to as “attendants” and anglers were conveyed up and down the river by horse and trap. The fishing was good both in terms of quantity and quality remembering of course that this was essentially a spring fishery between early January and the end of May. The best season was 1863 when a total of 1,510 salmon were taken, and when considering this figure compared with greater catches in very recent years, it should be remembered that there were only 7 or 8 rods at the most fishing, the tackle was far less effective than we now enjoy and they were virtually all caught in a period of some five months being prime springers with many double-figure fish amongst them including 20 and 30 pounders.

Dunbar was a shrewd businessman, and he soon recognised that to ensure the continued success of the venture he needed to have control not simply of the sports fishing on the river, but also that on Loch More (then much smaller in size than it is today the dam having not been built until the early 20th Century) and it was a fundamental part of the angling on the system being described as “the best Stillwater salmon fishery in Scotland” and providing more than 50% of the annual catch. Of perhaps even more importance was the need to control the commercial fishing, particularly the use of the netting cobble in the estuary which in a drought year could devastate the run.

He successfully dealt with these problems over the years up to 1869, by negotiating a series of new tacks or leases with the proprietors that gradually granted him not merely the angling rights of on the river and Loch More, but also the commercial fishing rights, including those in the estuary with the net and cobble and also the fixed engines that the proprietors operated in Thurso Bay. He persuaded them to build premises alongside the river at Halkirk (Braal Castle) and to include it in the letting to him as further accommodation for his anglers, as a result of which he developed the system whereby in the early part of the season from January to the end of March, when fishing was concentrated more on the lower reaches, they resided at Braal Castle, but from April until the end of May they moved up to Strathmore Lodge as thereafter the main focus for the fishing was on Loch More which was fished with boats, jetties having been built to accommodate them.

In 1861 he appointed a “Keeper and Fisherman” Rory Ross, and to a limited extent experimented with the possibility of damming up certain of the lochs feeding the river to create artificial spates and operating an artificial breeding programme introducing stock from the Tay and other rivers to improve the appearance of the Thurso salmon.

He was an innovator much ahead of his time, but contrary to what some commentators have said, he was not the person who stopped the netting on the Thurso. Far from it, he was a businessman who exploited it for profit, but in such a way as not to interfere unduly with the angling on the river and loch as he was very much aware that his anglers were suspicious about the effect of commercial exploitation on their sport and very early on made clear to him that unless he control that as well as the sports fishing they would not continue their rods. Of course, at that time, conservation was not the issue it is today.

However, towards the end of his life, he robustly rejected efforts made by Sir Tollemache Sinclair to take back the net and cobble in the estuary and fixed engines in the Thurso Bay, claiming that when he first took over angling on the river, the bay and Loch More were fished by the proprietor so severely that they gave the means of destroying his interests and those of his anglers.

He was extremely well liked by his angling and shooting tenants as well as the local community. Establishing a sports agency was a radical step but created a very sensible and effective way to run the river which, in its basic structure, continues to the present day although now, thankfully, with more availability to a wider section of the angling community than it had in his day. He made an immense and important contribution to the development of salmon angling on the Thurso and set a precedent that was followed on other highland rivers.

William Dunbar died at Braal Castle on 26 March 1879 (not as asserted by Grimble and Calderwood 1888) a comparatively rich man for the times and is buried in the graveyard at Halkirk where there is a memorial to him.

His final “tack” did not expire until 1888 and his business continue to be run by his trustees which included his widow who became the “tacksman” of his commercial fishery on the Berriedale not far from Thurso.

It is interesting to record that his Thurso enterprise was taken over, for a few years at least, by a syndicate that comprised of former clients who had fished the river under his management. They adopted the system that he had introduced, but did in fact stop exercising the netting rights. However, thereafter, they were reactivated and in the latter half of the 20th Century were carried on quite intensively.

A plea!

All my research has failed to reveal a photograph of him (albeit that there are photographs of his widow and children). If by any chance anybody can direct me to one I will be extremely grateful. Thank you.

Malcolm Dutchman-Smith is the author of A History of Salmon Fishing on the River Thurso

You can read our book review and how to buy yourself a copy HERE.